Climate must be factored into land acquisition for infrastructure development – Wendy Mlotshwa

Land requirements for infrastructure and trade-offs

Land is a complex and emotive topic in Africa; to understand it, one needs to grasp its ecological, cultural, cosmological, social, and spiritual importance, over and above its more obvious economic importance.

The subject becomes more poignant when considered in light of the large-scale dispossession and forced migrations of the past 200 years.

In addition to conflict and urbanisation, growing numbers of people are affected by climate-induced disasters. In 2022 climate factors – from drought to floods – forced over 250,000 people to leave their homes in the West and Central African regions alone, according to the International Organisation for Migration (IOM)[1].

Thus, the purchase or lease of large tracts of land by foreign nations, companies or individuals for infrastructure development or agricultural production is sensitive and needs to be managed in a transparent and fair manner. This is particularly the case in countries with lax legal frameworks or instruments for acquiring land, or within African countries where land is owned in communities and governed by customary laws.

History shows that there is a marked disparity in the benefits received by those involved in and affected by these large-scale land acquisitions, particularly for those originally living on the land[2]. Aside from the loss of physical shelter, there is the possibility of loss of assets or access to assets that impedes the ability to earn an income or sustain other means of livelihood[3].

For the financiers and developers of infrastructure in Africa, the Land-Livelihoods-Climate[4] nexus is well documented and understood, and serves as a guide for the planning, design, construction, and operation of any infrastructure. That said, the complexity and impact of infrastructure development on people is not to be underestimated. A 2020 study estimated that development-induced displacement and resettlement affects about 15 million people a year across the globe[5]. It is for these reasons that this article focuses specifically on displacement caused by infrastructure development and the impact of climate change on relocation decisions.

Land-Livelihoods-Climate Nexus

The effects of climate change have become more evident and unavoidable, adding to the need for more sustainable infrastructure to build resilience against climate exposure. However, this should not happen at the expense of local communities who sell their land to enable such development. There is a danger that in acquiring land for development, the displaced communities are exposed to more climate related shocks and stresses.

A better understanding of the implications of land use and transfers under the pretext of reducing the risk of climate-related disasters is required. For instance, in project development, a climate risk assessment should always be completed for the development itself, as well as on the replacement land.

In this regard it is not enough to provide replacement land or housing with security of tenure. Literature shows that while there is a strong link between secure land tenure and resilience to climate change[6], secure tenure on land that is susceptible to climate stresses can make landowners more vulnerable than they were before. Thus, security of tenure must go further than ensuring an individual holds legal title to the land – the identified parcel of land should also not be at risk of periodic climate related disasters. In addition to site selection, the housing built for the settled communities should provide the means to cope with climatic shocks; hence, the selection of construction materials, orientation of the building, structural design and building techniques to mitigate risk from natural disasters is imperative[7].

We can learn from previous mistakes. Literature is full of examples of resettlement programmes across Africa that have eroded people’s livelihoods due to loss of cultural identity, physical, financial, social, and natural assets. For instance, a well-intentioned project in Mozambique aimed to resettle 170,000 people from the Zambezi delta who had been affected by the 2007 floods. While government authorities deemed the scheme a success since it provided residents with secure land, critics claimed that living standards had deteriorated as a result. It must be added that the outcomes of resettlement are disproportionately felt by the vulnerable groups such as female headed households[8].

Cash compensation is often not an effective way of ensuring that displaced communities can restore or improve their livelihoods. Most rural communities lack the necessary skills to convert cash compensation into sustainable livelihoods. Sustainable living requires a combination of human capital, social capital, physical capital, natural capital, and financial capital.

The message is clear: the reconstruction and restoration of livelihoods is a long-term process. Research highlights the high levels of stress associated with relocation and notes that many resettled people choose to return to their original land if it is still accessible, while others migrate onwards[9].

There are success stories, however. A climate resilience project[10] in southwestern Mozambique saw people returning to the area after the introduction of irrigation and drainage systems raised the productivity of local farmers and boosted their ability to survive drought and floods.

Balancing community needs

There are synergies between climate and livelihoods, especially those that depend on access and availability of land, such as subsistence farmers. The difficulty is finding the balance between the need for development and the protection of community rights over land, especially considering climate change. As part of the resettlement process, developers must consider the climate risks that landowners or households will face. Research shows that the selection of suitable relocation sites receives very little consideration, with most of the focus on transferring the affected people away from their original location, without considering the factors that will secure their livelihoods.

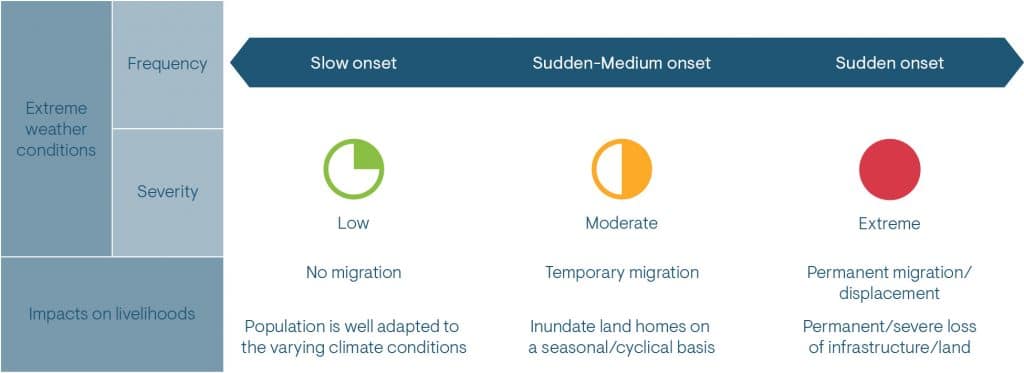

Replacement land should enable families to live sustainably, without being forced to relocate as their land becomes degraded by climate related change. The illustration below shows the impacts of climate change on livelihoods.

Figure 1: Adapted from Overseas Development Institute (2017)

Any resettlement or livelihood restoration project should aim to ensure that resettled people are not exposed to additional climate risks, as most rural livelihoods are agriculturally based and vulnerable to climate-related shocks. Regardless of the push factors, resettlement has inherent negative consequences.

Often these cannot be avoided. In these cases, communities should be provided with adaptive strategies necessary to buffer themselves against the impacts of climate change. For example, while relocating households near surface water resources for easy access to water for agricultural activities is ideal, it should not be done at the expense of exposing them to possible climatic threats such as fluvial flooding.

Community-Based Adaptation (CBA) is one of many solution pathways for strengthening the adaptive ability of vulnerable local communities to climate change. CBA can be defined as an approach that enables communities to improve their adaptive capacity and become more resilient to the effects of climate change. CBA programs take a participatory approach since they are drawn from local knowledge and customary adaptation processes and are representative of local culture or way of life [1]. This empowers the communities to act on climate change using their traditional knowledge.

There are many CBA programs that have been implemented across the continent to safeguard the communities and it would be recommended for developers to consider these as part of their resettlement strategies.

Examples include inter alia:

- Helping community members to diversify their income sources to lessen their dependency on land-based activities.

- Training communities on sustainable farming practices and use of climate resilient crops.

- Training communities on disaster risk management i.e., storage of food and water to cope with recurrent climate shocks.

- Use of incentive-based mechanisms such as Payments for Ecosystem Services (PES) programmes.

Mini case study: Payment for Ecosystem Services / Payment for Water Services scheme in Rwenzori Catchment, Uganda

Nyamwamba II hydropower project in western Uganda is a 7.8MW run-of-the-river that was developed by Serengeti Energy in 2022. The project is funded by Emerging Africa Infrastructure Fund (EAIF), a member of the Private Infrastructure Development Group (PIDG). Serengeti partnered with the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) to support the smallholder farmers who were impacted by the construction of the plant. The farmers were registered under the Payment for Ecosystem (PES) scheme to benefit from the programme and diversify their income.

The PES scheme is an incentive-based programme where individuals are compensated for maintaining or protecting ecological services (i.e., rehabilitation of catchment areas, forest conservation, carbon sequestration etc.) by those who benefit from these services.

The scheme has recruited well over 500 farmers, who aside from a small financial incentive, received farming equipment and training in sustainable land management (SLM). Farmers’ use of SLM led to the adoption of interventions that minimise erosion/ sedimentation and flooding hazards in the catchment area. In the process they provide the hydropower plants (including Nyamwamba II) with water flow of suitable quantity and quality while enhancing their own livelihoods[2].

Conclusion

Looking across the panorama of infrastructure investing, the importance of a climate lens in land acquisition and resettlement cannot be overstated. Development should continue in a sustainable manner without undermining the community integrity and wellbeing. In many cases the national legal framework that governs the land has proven to be ineffective in safeguarding the communities against climate related risks, as there is no clear link between their climate strategies and land policies. The legislation is fragmented.

It is incumbent upon infrastructure investors and project developers to ensure that climate is factored into land acquisition processes, thus safeguarding the livelihoods of communities that may end up bearing the brunt of climate shocks.

[1] https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/publications/CBA%20Community%20based%20adaptation%20to%20CC.pdf

[2] https://dtnac4dfluyw8.cloudfront.net/downloads/new_strategy_bklet_pat_v2.pdf

[1] https://www.iom.int/news/face-climate-change-migration-offers-adaptation-strategy-africa

[2] https://www.brookings.edu/articles/african-land-grabbing-whose-interests-are-served/

[3] as defined in the IFC Performance Standards 5 Guidance Note

[4] Climate Variability Impacts on Land Use and Livelihoods in Drylands

[5] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7320115/

[6] https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/documents/2019-06/un-habitat-gltn-land-and-climate-vulnerability-19-00693-web.pdf

[7] https://wedocs.unep.org/xmlui/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/36405/Adapbuild.pdf

[8] Clause 19 of the IFC Performance Standards 5 Guidance Note acknowledges this disparity and necessitates paying special attention to these groups.

[9] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0305750X21003922

[10] https://www.afdb.org/en/news-and-events/first-flood-then-drought-climate-resilience-project-helps-farmers-thrive-mozambique-36790